#MeToo, one year on. What can the aid sector learn?

The aid community is actively working to achieve gender equality and empower women girls. But it’s also part of the problem.

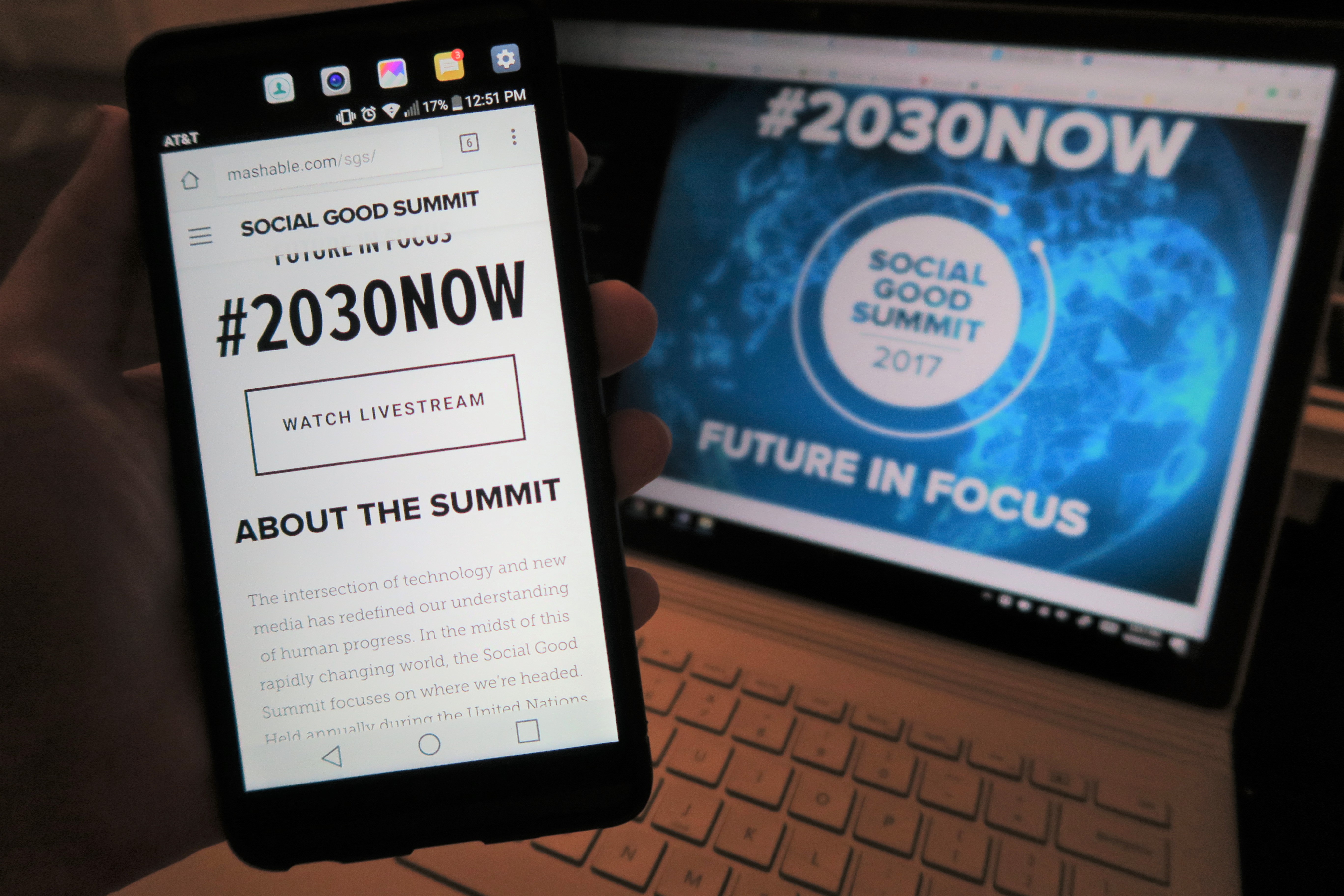

Joanne Smith, Fatima Goss Graves, and Monica Ramirez speak at the Social Good Summit. Image source: United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative

Content warning: This piece discusses sexual and gender-based violence, including sexual harassment and assault.

________________

On October 5th, 2017, Harvey Weinstein was publicly accused of sexual assault.

Ten days later, Alyssa Milano sent the tweet that ignited the #MeToo movement. Within 24 hours, millions of people from 85 countries had engaged with #MeToo on social media.

The onslaught of sexual misconduct accusations that have followed, dubbed the Harvey Weinstein effect, have toppled dozens of high-profile Hollywood men. One year later, the #MeToo movement is still in full swing.

While star-studded accusations have received the most airtime, Hollywood is far from the only sector where sexual harassment and assault are pervasive: #MeToo has permeated all spheres of society, including the business world, the Senate, and even the Supreme Court.

Last February, the aid community was reminded that even the very industry that purports to empower women and girls is not immune to sexual misconduct when reportssurfaced that several Oxfam staff responding to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti “engaged in sexual exploitation and bullying, including paying vulnerable women for sex.” Suddenly, the #AidToo movement was born.

Around the same time, Save the Children became embroiled in allegations that it failed to investigate inappropriate behavior by senior staff, including sexual harassment of employees at the agency.

300 cases of sexual abuse, including against children, were carried out by UN peacekeepers and civilian staff in 2016.

And as recently as a few weeks ago, a senior U.N. gender and youth official was fired for sexual misconduct, re-igniting the #AidToo conversation.

Sexual and gender-based violence is pervasive, and the aid industry is no exception. So how can we take the experiences of the past year and leverage them for change? How can we safeguard beneficiaries and employees of development organizations?

Last week, the Social Good Summit drew a diverse melting pot of passionate changemakers, including policymakers, activists, development practitioners, students, chefs, YouTubers, a Prime Minister, and a Nobel Prize Laureate.

Among them were Fatima Goss Graves, President and CEO of the National Women’s Law Center; Monica Ramirez, Founder of Justice for Migrant Women; and Joanne Smith, Founder and Executive Director of Girls for Gender Equality; who discussed the progress of #MeToo over the last year and the future of the movement.

Here are three lessons the aid community can take from these women to address sexual assault and harassment in the sector and safeguard beneficiaries and staff.

1. Safeguarding and support for survivors.

For Graves, the most inspiring thing about the past year is “the many, many people who continue to name their experiences and come forward.”

But all too often, survivors and whistleblowers who report abuse in the aid sector are met with opposition rather than support. And for instances of abuse within the UN system, cases tend to drag on for years before being resolved as the process passes through multiple U.N. bodies, taking a severe emotional toll on survivors.

Experts maintain that the majority of sexual assault and harassment cases are never reported, and it is not difficult to understand why. Organizations in the aid sector should prioritize adopting a survivor-centered approach that proactively facilitates supportive, secure safe spaces for survivors to share their experiences, own their own narratives, and be heard.

As Ramirez expressed, “We all deserve to live and work with safety, security, and dignity.”

2. Accountability

Graves expressed the importance of holding institutions accountable for their actions. “I am deeply focused on making sure the many institutions that do not want to change understand that they must,” she asserted.

According to a recent report from the International Development Committee that examined alleged abuse from aid workers and United Nations peacekeeping troops of both beneficiaries and fellow staff, aid organizations have been “sluggish,” “delusional,” and “verging on complicity” with perpetrators when addressing allegations of abuse.

Organizations in the aid sector must be held responsible for publicly reporting all allegations of assault and harassment and the steps they are taking to address them, regardless of whether the allegations may be damaging to an organization’s reputation. Transparency is crucial if the public hopes to hold aid groups accountable for their actions.

3. Getting to the root of the problem.

According to Smith, “We have to get to the root of the root of the problem and address it holistically.” In order to make real progress, aid groups must target the power dynamics, behaviors, and social norms that enable a culture of abuse to thrive.

This will be no easy task: Sexual abuse and exploitation are complex, multifaceted issues that are deeply entrenched in the fabric of our society.

Still, the palpable dialogue taking place surrounding sexual harassment and assault is undoubtedly transforming social perspectives about these issues.

So what does Smith have to say about the future?

“It’s clear that we’re not going back.”

________________

Sarah Allen (@saraheallen_) is a Communications Associate at BRAC USA with expertise in international education, youth empowerment, and development economics. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in International Relations from Western Washington University, and now resides in New York City.