UNESCO Programs and Their Value to the World Today

Vernon (Tom) Gilbert has had a devotion to the conservation of natural resources, and international communication in support of that, for more than 70 years since his first job as a seasonal naturalist at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In 1973 Tom went to UNESCO in Paris where he worked with colleagues to develop the ideas for the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program, and became US MAB Coordinator upon his return to the US. Since his retirement from the National Park Service in 1980, he has been focused on UNESCO conservation programs, with a goal to harness and protect ecosystems and the genetic resources they contain. Throughout his life Tom has been focused on developing relationships throughout the world to advance these goals.

Chris Groves was introduced to UNESCO through his friendship with Professor Yuan Daoxian in 1995, who invited him to collaborate with UNESCO’s International Geological Correlation Program (IGCP, now the International Geoscience Program). Since 2008 he has served on Board of Governors for the Category II International on Karst Under the Auspices of UNESCO in Guilin, China. As a University Distinguished Professor of Hydrogeology at Western Kentucky University, since 1982 he has worked closely with Mammoth Cave National Park, both a World Heritage Site and an International Biosphere Reserve. In September he will represent the US Biosphere Network at the World Congress of Biosphere Reserves in Hangzhou, China.

1. Abstract

In 1945, at the end of the most destructive conflict in human history, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was established, mindful that “ignorance of each other’s ways and lives has been a common cause, throughout the history of mankind, of that suspicion and mistrust between the peoples of the world through which their differences have all too often broken into war.” In 1968 a vision emerged that conserving the world’s ecological resources, and the genetic material they contain, could fundamentally help to sustain the “defenses of peace.”

Here we describe value that international communication has had on the science and practice of protecting the world’s most precious places, natural and cultural, and the central place of UNESCO in this history. We draw on our own experiences, particularly through the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) program, which for Tom now goes back now more than 50 years.

Ideas discussed during the 1968 Paris UNESCO Intergovernmental Conference for Rational Use and Conservation of the Biosphere led to the birth of MAB establishing “a scientific basis for enhancing the relationship between people and their environments” and a world network of biosphere reserves as a means to “keep options open for the future.”

Nurturing synergy among groups with common goals in the international natural resource protection and geoheritage communities is as critical as ever. There are several distinct efforts, though with some overlap, including the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere programs and World Heritage programs and the George Wright Society, among others, and we hope that increased communication and visibility of these efforts will lead to cooperation and enhanced effectiveness. We propose that the United Nations Association of the United States of America (UNA-USA) could bring many groups and individuals together in support of this cause. Our purpose is to encourage UNA leadership and members to engage with UNESCO area programs here in the U.S. and internationally

2. Introduction and Background

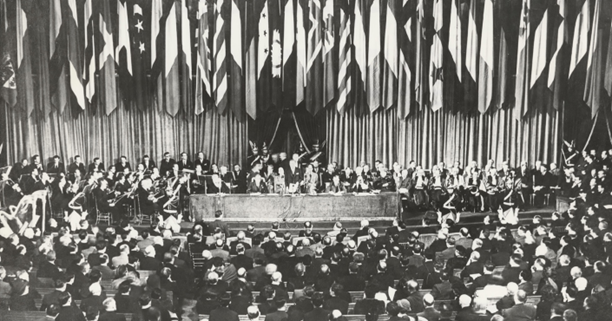

In November of 1945 a group of diplomats met in London, England, in the immediate aftermath of the most destructive conflict in human history. They looked around and wondered about what could encourage a world where nothing like this could ever happen again. What emerged from this meeting was a new organization, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The preamble of its constitution (UNESCO 2024, Figure 1), adopted on November 16, 1945, was written by the poet Archibald MacLeish who wrote that “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed,” and that “ignorance of each other’s ways and lives has been a common cause, throughout the history of mankind, of that suspicion and mistrust between the peoples of the world through which their differences have all too often broken into war.” UNESCO was created “for the purpose of advancing, through the educational and scientific and cultural relations of the peoples of the world, the objectives of international peace and of the common welfare of mankind for which the United Nations Organization was established and which its Charter proclaims.”

In this paper we describe our experiences with UNESCO programs—in particular those with a focus on protection and conservation of the world’s most precious natural and cultural resources –-and our understanding of their values in the world today. We urge efforts to find synergy among different groups that have common goals in the international conservation and geoheritage communities, and we propose that the United Nations Association of the United States of America (UNA-USA), in cooperation with the United Nations Foundation, could bring many groups and individuals together in support of this cause.In this discussion we especially draw on the experience gained by our interactions with many scientists and conservation leaders in the planning and development of UNESCO programs and related conservation efforts. There are lessons from these programs that can be useful today. For example, the task group of experts that Tom’s colleagues and he convened in Paris in 1974 to design guidelines and criteria for a world network of biosphere reserves thought these sites served as a means to keep options open for the future by conserving genetic materials essential for life and human well-being (UNESCO 1974). This goal cannot be achieved under the current

circumstances because of increasing problems such as international abuses of power, wars, and displacement of people. It is obvious now that “keeping our options open for the future” through the protection of natural resources and the genetic material they contain cannot be achieved if we fail in promoting peace and security. There are sensible ways to address the threats to precious and sensitive areas and the options for dealing with them.

Tom grew up in the Great Smoky Mountain area and fell in love with the beauty and variety of plant life in that region, which was established as the Great Smoky Mountain National Park in 1936. He has clear memories of sitting on a grassy bank in Knoxville, TN of waving to a smiling President Franklin Roosevelt on his way to designate the National Park in 1940. In his dedication speech at Newfound Gap on the Tennessee-North Carolina border, the President warned of the growing dangers of the world, that there were shadows that Tom knew little about. Pearl Harbor, just fifteen months away, and the US entry into World War II changed all that.

3. UNESCO Paris, 1973–1975

During the 1972 Second World Conference on National Parks in Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Park where Tom’s staff conducted the interpretive program, then Director of UNESCO’s Ecology and Earth Sciences Division Michel Baptiste noted that the launching by UNESCO of the international research program on Man and the Biosphere (MAB) would constitute another important tool for the establishment and preservation of biological reserves, and, indirectly, of national parks. Dr. Baptiste requested assistance from the US National Park

service and director George Hartzog agreed to help (Elliott 1972, p. 417). Tom was selected for this position. At the Yellowstone conference Tom presented a paper A Widening Horizon—The Role of Parks and Reserves in Education. This was a theme he pursued to ensure that education and training were given high priority when he joined UNESCO (Elliot 1972, p. 358-373). Tom’s colleagues and he were able to convene a Task Force on Criteria and Guidelines for the Choice and Establishment of Biosphere Reserves (UNESCO 1974). When the taskforce’s report was completed, the US/USSR agreement that Tom had proposed created world-wide attention.UNESCO’s Director General then wrote to Henry Kissinger, and the State Department sent communiques to all members of the UNESCO International Coordinating Council (ICC). This communique stated the following:

Desiring to expand cooperation in the field of environmental protection,

which is being successfully carried out under the U.S./U.S.S.R. agreement signed on May 23, 1972, and to contribute to the implementation of the “Man and the Biosphere” international program conducted on the initiative of the United Nations, Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), both sides agreed to designate in the territories of their respective countries certain natural areas as biosphere reserves for protecting valuable plant and animal genetic strains and ecosystems, and for conducting scientific research needed for more effective actions concerned with global environmental protection. Appropriate work for the implementation of this undertaking will be conducted in conformity with goals of the UNESCO Program and under the auspices of the previously established U.S./U.S.S.R. joint committee on co-operation in the field of environmental protection.

The establishment of the United Nations in 1945, and of its various specialized agencies in the years that followed, indicated a willingness of government to act in concert in efforts to solve major problems confronting the world. No one would pretend that the United Nations has functioned in all the ways that the founders of this organization had hoped. Many have suggested ways in which the United Nations could be improved. Nearly all would agree, however, that if the United Nations systems were to cease to exist an organization very similar to it would have to replace it immediately. The willingness of nations to work together toward certain common goals is apparent. One goal on which all nations can agree is the need for maintaining and improving the human environment. The United Nations and its specialized agencies represent means by which governments can work together towards this goal.

The Biosphere Conference held in the UNESCO House in Paris in 1968 was a major step forward for the United Nations system. It represented the first major intergovernmental conference directed toward the solution of the problems of the biosphere in its totality. The principles affecting the rational use and conservation of the resources of the biosphere were brought under critical review. Based on the information presented, the representatives of the nations that were in attendance agreed on a series of recommendations for future action. The problems discussed thus far in this book were generally recognized, and the need for all governments to join in a broad program directed toward their solution was stressed. UNESCO was called upon to take lead in forming a scientific research program that would carry on from where the International Biological Program left off, but with the full support of governments and of the United Nations specialized agencies.

Following the Biosphere Conference, work was begun at UNESCO which led to the drafting of a major, long-term research effort that became known as the Man and the Biosphere program, or MAB. This was done, as all such things must be, through a series of consultations with the member states of UNESCO, with the specialized agencies of the United Nations system, and with concerned nongovernmental, international agencies such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU).

A major advance in the global drive to improve and maintain the environment was announced by the four main international organizations concerned with nature conservation, during a second meeting in July, at Morges, Switzerland.

On the initiative of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), have agreed to form an Ecosystem Conservation Group to help coordinate their efforts relating to nature conservation and ecosystem conservation in particular.

4. Continued Evolution of These Ideas

When Tom returned from Paris in 1975, he became the United States MAB Program Coordinator. The 14 MAB project areas at that time focused on the environmental impacts of increasing human activities on different ecosystems including tropical and subtropical forests, temperate and Mediterranean landscapes, savannas and grasslands, mountains and tundra, and coastal zones. Processes associated with human impacts were studied, including fertilizer use, urban energy utilization, and environmental pollution. There is also a legacy today that evolved from the project on Conservation of Natural Areas and of the Genetic Material They Contain (McCormick and Kormondy 1981).

Although the trajectory of political support for the MAB program varied through different administrations, the ideas continued to grow, very much informed by Tom’s experiences in conservation throughout the world. In 1982, he became Field Director of the Environmental Training and Management Project in Africa, where he was able to initiate cooperative regional projects in several countries. Under the US Agency for International Development (USAID) supported Environmental Training and Management Project in Africa (ETMA), from 1982 to 1984 Tom and his colleagues established cooperative activities on conservation of plant communities in East Africa (Figure 3), which they called “Endangered Resources for Development.”

Kenya’s President, Daniel Arap Moi, endorsed this program, stating in the forward to the ETMA report that “Historically our natural environment has provided the people of Kenya with food, fuel, building materials, and often medicine … It is still vital

today and it will remain so in the future. It is the duty of us all to take action now, while there is still time, to halt the destruction of plant and animal species, to conserve special areas of vegetation, and to enforce a proper balance in the utilization of these natural resources” (USAID 1984).

Another cooperative demonstration program was conducted in the Virunga Volcanoes Mountains

of Northwestern Rwanda (Figure 4) which had been designated as a biosphere reserve. This was the country’s most important watershed as well as the home of the mountain gorilla. Farmers had encroached on the reserve clearing forests and causing extensive erosion and mud slides, and so a cooperative project was established to help farmers control erosion, sustain their farms, and protect the home of the mountain gorilla, which was considered a resource for the world.

In 1983 at the First Biosphere Reserve Congress in Minsk, Byelorussia/USSR, Tom presented a paper Cooperative Regional Demonstration Projects: Environmental Education in Practice. This paper recommended support to UNESCO for 1) the establishment of biosphere reserves and 2) to assist countries in the selection and development of such Cooperative Regional Demonstration Projects (CRDP’s) by designating and making available necessary technical experts to UNESCO MAB.

As an initial model in the US, the Southern Appalachian Man and Biosphere (SAMAB) program was established in 1988. The White House Council on Environmental Quality had given special recognition to SAMAB, significant because the CEQ had major responsibility for advancing environmental priorities of the United States. These included climate change, conserving lands and waters, and ensuring implementation of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). SAMAB demonstrated how public and private land and water managers could share joint decision-making on a regional scale.

In 1998 Tom prepared a booklet on Plant Genetic Resources: Their Conservation In Situ for Human use, because in 1983 at the 22nd FAO conference in Rome, there had been an international undertaking on plant genetic resources which aimed to ensure that plant genetic resources of economic and social interest would be studied, conserved, evaluated, and made available for plant breeding and scientific purposes.

The booklet concluded that “The stress on renewable natural resources is already undermining the ability of land in many areas of the world to produce the goods and services necessary for human well-being; and making it more prone to drought, erosion, and desertification. Unless this stress is curtailed, it will impose severe limits on economic growth and development in the future,” and that “The remaining years of this century are of critical importance for the conservation of genetic resources, especially in the tropics; time to act is rapidly running out. It is essential that the challenge facing us is vigorously confronted, to ensure the well-being of present and future generations. The financial resources and expertise must urgently be mobilized, as the IUCN and (World Wildlife Fund) WWF plant campaign puts it, to “save the plants that save us.”

There is, in some aspects, an appalling lack of care about our major food crops and what it takes to sustain them. Some of our most important introduced food species include corn (maize), wheat, rice, potatoes, tomatoes, soybeans, and many fruits including apples, oranges, bananas, mangoes and avocadoes. All of these are originally from other parts of the world and still rely on genetic resources from these areas to sustain global food production. How many of the millions of people who drink coffee every day, for example, know that Arabica coffee originated in the Ethiopian region of Africa and that two biosphere reserves have been established to conserve and restore the remaining wild coffee forest? How many know about the turmoil that Ethiopia has gone through for decades?

5. UNESCO Programs

One of the greatest threats is war. UNESCO was created in 1945 to work towards peace, education, science and cultural needs and today has a program on Global Citizenship and Peace Education. The United Nations was also created in 1945. Today one of the best programs we have for nurturing requisite relationships is the UN Association of the United States of America (UNA-USA). Their mission is “dedicated to educating, inspiring, and mobilizing Americans to support the principles and vital work of the United Nations and its specialized agencies such as UNESCO.” The UNA-USA can be a means to bring hundreds of groups and thousands of individuals into a more effective effort to work for peace and sustainability. The UNESCO MAB, Global Citizenship and Peace Education Programs, and the UNA-USA can help to educate a new generation of statesmen and Women. As Mark Brennan, who was recently awarded the UNESCO Janusz Korczak Jubilee Medal for his work with human rights, youth rights, and education for peace, describes, for example,

The UNESCO Chair on Global Citizenship Education for Sustainable Peace at Penn State University focuses on building community capacity to advance peace and the establishment of stable, civil societies. Central to this is the active engagement of youth as central players in this process. Through our work we seek to build global citizenship, social-emotional competencies (empathy, compassion, mindfulness), and informed youth voice (rigorous youth led research). All are designed to lead to action by empowered global citizens. Such action has taken the form of youth and community led initiatives around social justice issues, the formation of programs and policy to promote active citizenship, and programmatic efforts to bridge the divides present with our societies.

The world network of Biosphere Reserves now contains 759 sites in 136 countries (Figure 5) and 28 in the United States. In addition to protecting biodiversity in parks and protected areas, biosphere reserves include landscapes where people live and work. Public and private organizations work to ensure that communities prosper and maintain healthy lands and water through sustainable tourism, farming, forestry, fishing and other economic uses.

This network is an ideal place to initiate citizenship, natural resource sustainability and peace education in the thousands of institutions associated with the World Network of Biosphere Reserves, World Heritage Sites and many national parks. These biosphere reserves are ideal places to understand the threats to sustainability and the options for dealing with them. A major threat in many places is armed conflict and competition for natural resources. There are hundreds of organizations and thousands of individuals working to achieve these goals through their separate and often isolated actions. We hope that increased communication and visibility about the programs of these international conservation goals can lead to synergy and efficiencies. There are a variety of distinct organizations and networks, with some overlap and broadly similar goals, objectives, and approaches within UNESCO (Man and the Biosphere, World Heritage, Global Geoparks, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands), and outside UNESCO such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), George Wright Society, U.S. Biosphere Network, World Heritage USA and other entities.They could become a more powerful force if they worked together, and the UNA-USA is an excellent opportunity to cooperate and to determine how a new generation of statesmen and women could help keep options open for future generations. All of us should encourage people, and especially young people, to join UNA-USA. Using Biosphere Reserves to conserve natural and cultural diversity, and especially for in situ conservation of genetic resources, including wild relatives of cultivated and domesticated species, and considering use of the reserves as rehabilitation/ re-introduction sites, and linking them as appropriate with ex situ conservation and use programs (UNESCO 1995). By combining in situ and ex situ approaches to conservation of genetic resources, many more species can be secured and made available for human use. This would be a significant contribution to food crops, sustainability and security.

The communication of these ideas throughout the world also has great benefits, as people better understand one another, as a powerful form of diplomacy.

6. A Closing Thought: Conservation and Peace

After World War II, Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin, and Franklin Roosevelt met at Yalta, Crimea, to shape the post-war peace (Preston 2019). Roosevelt (Figure 6) endorsed the creation of a new organization—the United Nations—to create a lasting framework for cooperation, and thus security, among the world’s nations, and in this way to prevent future wars.

By April, while planning to attend the upcoming conference in San Francisco where the United Nations Charter would be created, Roosevelt, whose health had been failing, retired to his retreat at Warm Springs, Georgia to rest and write. Preparing for a nationwide radio broadcast a few days later Roosevelt, on the night of April 11 wrote the words below (Hathaway and Shapiro 2023). He died later that evening and was never able to deliver the address, but his thoughts remain, and must continue to inform our thinking today:

The work, my friends, is peace, more than the end of this war—an end to the beginning of all

wars, yes, an end, forever, to this impractical, unrealistic settlement of the differences between governments by the mass killings of peoples.

This is the United Nations, and this is UNESCO.

References

Elliott, H. 1972. Second World Conference on National Parks, Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, U.S.A. September 18-27, 1974. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

Hathaway O.A. and S.J. Shapiro. 2023. “The internationalists: how a radical plan to outlaw war remade the world.” Leading Works in International Law. Routledge.

McCormick J.F. and E.J. Kormondy 1981. Handbook of Contemporary Developments in World Ecology. Greenwood Press.

Preston, D. 2019. Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World. Atlantic Monthly Press.

UNESCO. n.d. “UNESCO in Key Figures.” Accessed June 16, 2025. https://www.unesco.org/en/key-figures.

UNESCO. 1974. “Report of the Task Force on Criteria and Guidelines for the Choice and Establishment of Biosphere Reserves.” Accessed June 23, 2025. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000009889?posInSet=1&queryId=6e2abab0-687f-4ff3-803d-427edfabee7b.

UNESCO. 1995. The Seville strategy for biosphere reserves. Accessed June 25, 2025. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000262500

UNESCO. 2024. “Constitution.” Accessed June 23, 2025. https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/constitution.

USAID. 1984. Environmental Training and Management Project 1984, Endangered Resources for Development. Report, US Agency for International Development.